Showing some sensitivity toward the perpetuation of terribly racist branding, consumer products companies have recently chosen to re-brand themselves. The first to do so in September 2020 was the former Uncle Ben’s line of rice dishes marketed by Mars, Incorporated (see “Uncle Ben’s Changing Name To Ben’s Original After Criticism Of Racial Stereotyping”). Next it was Quaker Oats’s Aunt Jemima brand of baking mixes, syrups and prepared breakfast foods (see “Aunt Jemima finally has a new name”). Mars chose “Ben’s Original” for its new brand; Quaker Oats opted for “Pearl Milling Company” as a replacement for Aunt Jemima. While these moves should perhaps be applauded, both for their cultural awakening and as public relations victories, some PR professionals will say that their industry is in dire need of an awakening–particularly in the hidden hallways, offices and cubicles of PR offices.

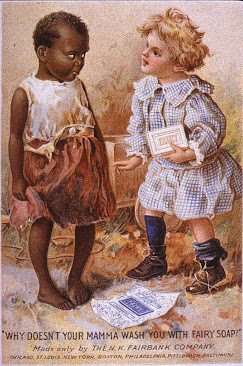

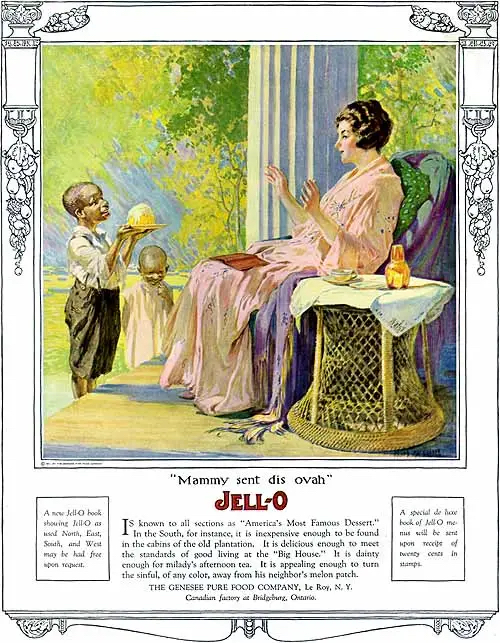

Clearly, getting rid of racist branding is a positive step toward the sensitive treatment of race in commerce. In a statement, Mars said, “We understand the inequities that were associated with the name and face of the Uncle Ben’s brand … We have committed to change.” A Quaker Oats spokesperson struck a slightly different tone, saying in part “We are starting a new day with Pearl Milling Company. A new day rooted in the brand’s historic beginnings and its mission to create moments that matter at the breakfast table.” Interestingly, the comment seemed to focus on the “breakfast table” rather than openly acknowledging a break with the “ugly truth behind Aunt Jemima” (see “New Racism Museum Reveals the Ugly Truth Behind Aunt Jemima”). Of course, though it seems desirable to praise these kinds of changes, it might be good to bear in mind that sales of rice, pancakes and syrup might be the ultimate goal of such re-branding.

Although these may be seen as solid PR victories in the battle of vicious racial stereotypes, the same can’t be said for how race is managed inside PR shops. Some seem to be less than diverse. PR professional Jo Ogunleye points this out in a blog post on her experiences as a practitioner (see “Black Lives Matter: from one Black PR to the industry”). “Throughout my entire PR career, from my first internship to today, across in-house and agency, and in both public and private sectors, I have only ever had two jobs with another Black person in my team,” she says. “I have never had a Black boss.”

Statistics seem to back up her claim. A 2018 Harvard Business Review analysis of federal labor statistics found the industry is 87.9 percent White, 8.3 percent African-American, 2.6 percent Asian American, and 5.7 percent Hispanic or Latinx. Increasing diversity might start in the classroom. As Kelsey Landis, editor-in-chief of INSIGHT Into Diversity points out, more must be done to make university public relations programs more diverse, including making minorities more aware of public relations as a career path (see “The Public Relations Industry Is Too White and the Solution Starts with Higher Education”).

So it seems that when it comes to dealing with race, there are some issues that PR as an industry is getting right; on the other hand, there’s still room for much improvement, particularly among the ranks of PR professionals. That there is room for improvement begs the question: Does PR’s lack of diversity cast a shadow over how it has responded to the managing of brands? Moreover, what can be said about Landis’s claim when it comes to Creighton University; or, for that matter, our own Department of Computer Science, Design and Journalism?